Okay, let me tell you about Miranda July’s 2005 film, Me and You and Everyone We Know. It’s a really interesting, but also quite polarizing, movie. July dives headfirst into some pretty taboo subjects, really examining how we all approach sex and relationships. What struck me most was how deeply it explores loneliness and the way we tend to put people on pedestals. Before this, July was known for her quirky short films and performance art, and you can definitely see that influence here. Her character, Christine – a video artist who drives around and keeps senior citizens company – feels like a direct extension of her earlier work. It’s definitely a film that will get people talking, but be prepared – it’s not for everyone.

The film centers on the uneasy connection between Christine and Richard, a man recently separated from his wife, portrayed by John Hawkes. Christine longs to be recognized as an artist and to find a fulfilling relationship, while Richard is adjusting to life with a new family. Their connection is complicated by both attraction and a desire to avoid loneliness, a theme that runs through all the characters. From children to seniors, the movie explores how society shapes our understanding of love, sex, acceptance, and rejection.

Me and You and Everyone We Know Explores Innocence and Loneliness

Even twenty years after it came out, Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know still offers a powerful look at a side of life people often don’t talk about – and it might be even more relevant today, as kids get online at younger and younger ages. The film asks tough questions about why people behave the way they do when they’re attracted to someone, even challenging our understanding of what love actually is. It suggests that attraction might simply be copying others and following established patterns – a way to avoid the painful feeling of being alone. We see this throughout the movie, from Christine’s idealized view of Richard to young Robby’s online interactions – all the characters are constantly mirroring the behavior of others.

A central idea in the movie is that people generally learn about sex by watching and copying what they see around them. However, when society avoids talking about sex openly, everyone feels confused and ends up blindly following each other. The film explores innocence – not just in children, but also in adults – which has been controversial for some viewers. Some have criticized the director, Miranda July, for suggesting even those who commit harmful acts can possess a degree of innocence. But this is an oversimplification. The movie realistically and satirically portrays pedophilia as a symptom of a bigger problem: a society where adults lack understanding of their own sexuality, often due to past abuse.

Watching scenes involving inappropriate interactions between children and adults can be deeply unsettling, and some viewers may be unable to look past this discomfort to understand the film’s overall message. However, the movie isn’t focused on sexual content; instead, it powerfully illustrates the dangers children face from predatory adults, both online and in person. While the film does explore the humanity of these criminals and acknowledges a child’s natural curiosity as a contributing factor to risky situations – a choice some may find difficult – it strives for realism. Characters like Richard’s coworker, who harasses teenage girls, and the museum curator, who unknowingly connects with a young child online, are portrayed as profoundly lonely individuals, lost and unable to function normally in society. They act on harmful impulses, but ultimately find themselves unable to fulfill their own desires, revealing the emptiness behind their behavior.

The children and teenagers are all naive about love and sex, lacking real understanding but filled with ideas from movies and stories. Sylvie dreams of being a traditional wife and mother, while Christine fantasizes about a perfect first encounter with Richard. The girls try to attract male attention, mirroring how even an adult, like the art curator, can get caught up in superficial interactions. These shallow experiences highlight how difficult true connection is, a theme embodied by Christine’s constant pursuit of Richard, who desperately wants intimacy but struggles to achieve it.

The Movie Depicts a Community Shaped by How Individuals Feel

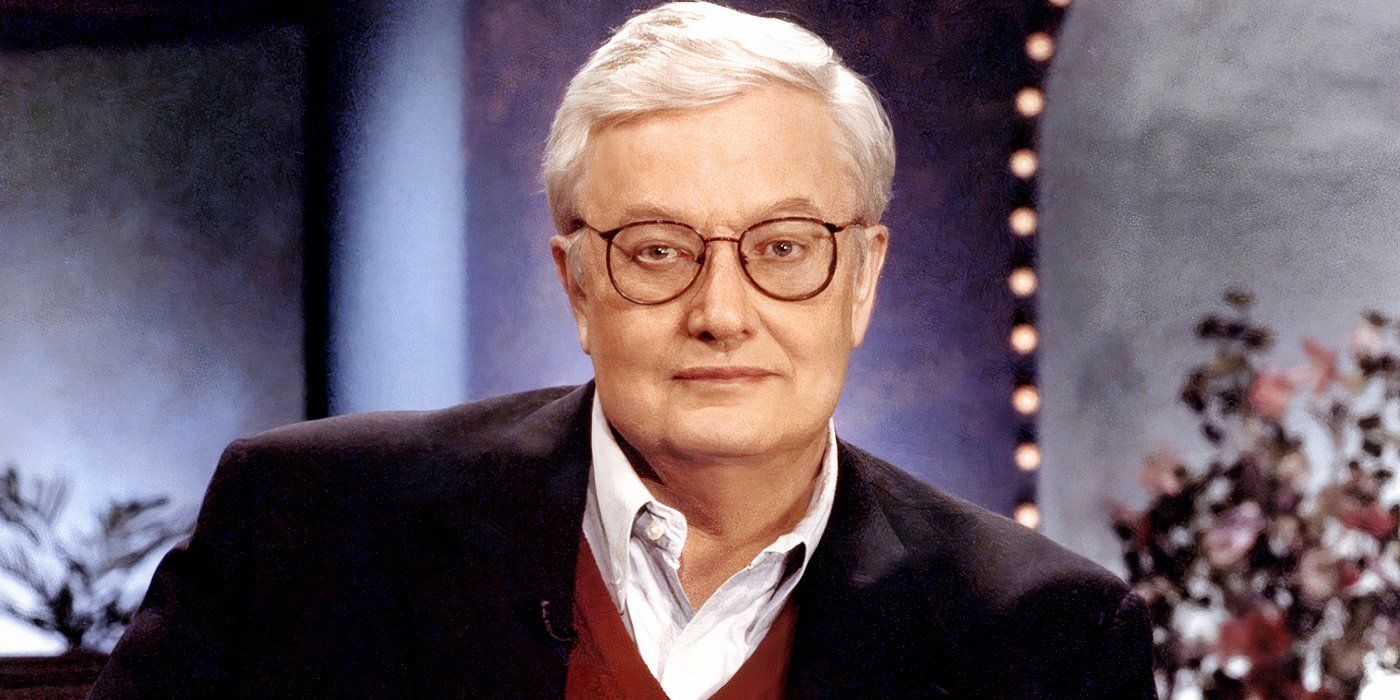

What truly sets Me and You and Everyone We Know apart is its ability to find deep meaning in everyday moments. Film critic Roger Ebert hailed it as the best film at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival and one of the decade’s best, noting how the film bravely explores complex themes with a unique honesty and acceptance of human behavior. Though some scenes might initially seem unrelated to the main story, they cleverly reinforce the film’s overall message about people and their nature.

Christine often faces situations where she tries to help, even when success is unlikely, like when she and a client attempt to save a dying goldfish. This mirrors the helplessness she feels with her client Michael, whose partner is seriously ill. She recognizes a similar pattern in her own life, realizing that even in relationships, like the one with Richard, there’s always a moment when you understand the connection won’t last forever.

The movie doesn’t just focus on what individuals are feeling; it shows how those feelings connect to create a larger community. It subtly reveals whether that community is thriving or struggling. A small scene perfectly illustrates this: Richard tells his son, Peter, they live in a community, but doesn’t mention the neighbor is only offering Peter a ride because Richard gave her a family discount on shoes. This hints at the hidden connections and unspoken obligations within the community. We see these connections throughout the film – Richard’s coworker is secretly involved with some teenage girls, who then secretly enlist Peter’s help with a project. Even young Sylvie has her secrets, quietly observing everything and only sharing her desire to get married with Peter.

The film follows a complex web of connections. The art curator dismisses Christine professionally, yet privately appreciates her talent. Meanwhile, she’s having online conversations with someone she believes is an adult, only to discover it’s a child. These hidden relationships – involving debts and a child’s awakening – force the movie to ask questions about the nature of the community these characters, and us as viewers, inhabit.

The Movie Raises Interesting Questions About Gender

Beyond the way the movie avoids traditional gender roles, I noticed some really interesting, subtle things about how it portrays men and women. It felt like everyone was deeply insecure, but that insecurity played out in different ways depending on their gender. The women and girls, especially, seemed to be constantly sizing each other up – almost like they were trying to figure out who was ‘better’ at being a woman. You see it in how the teenage girls act, and even in Christine’s jealousy of Richard’s ex-wife, even though they’re clearly done with each other. But the men and boys seemed to be stuck in a cycle of trying to be like each other. Peter showing Robby the ropes with online chat is a good example, and it reminded me of Richard trying so hard to be the ‘cool uncle’ – even to the point of hurting himself.

Even if we don’t see who these individuals are copying, their behavior still shows they’re influenced by outside sources. The teenage girls are acting in a competitive way that aligns with societal expectations for women – trying to please men rather than prioritizing their own satisfaction. Similarly, the man they’re interacting with is displaying behavior that fits within the same harmful social norms. Neither group is questioning why they’re acting this way, which keeps this damaging pattern going.

A seemingly minor storyline involves an art curator and a visual artist collaborating on an installation. The curator appears secure when interacting with another woman, Christine, but reveals her insecurities when dealing with the male artist. Interestingly, this unnamed male artist is the only character who seems truly self-assured. However, his confidence isn’t based on authenticity; he understands society is performative and simply mimics others without needing to appear genuine.

Trying to tackle big questions about life, relationships, and intimacy in a single film is a challenge. While Miranda July frequently touches on sexuality in her movies, this film marked her first real attempt to deeply explore the subject. She’s said she’s always been fascinated by sex – not just the act itself, but also the emotions it brings up, like embarrassment, desire, and vulnerability. July’s sensitive and insightful approach to this often-sensitive topic is what sets her work apart, and this movie remains a powerful illustration of how complex and layered sex can be.

Read More

- Золото прогноз

- Прогноз нефти

- Падение Bitcoin: Что вам нужно знать сейчас!

- 40-летний танец Bitcoin: Смешная долгосрочная ставка исполнительного директора.

- Доллар обгонит рубль? Эксперты раскрыли неожиданный сценарий

- Captain America 4: See What Diamondback Villain Would Have Looked Like

- Percy Jackson Season 2’s Tyson Explained: Everything You Need To Know About The Cyclops Character

- Провал XRP в ноябре: Крипто-клоун криптовалюты!

- Pedro Pascal Set to Steer Avengers as Reed Richards in Shocking Marvel Shift!

- Could KPop Demon Hunters Get A Live-Action Movie? The Directors Have Shared Their Thoughts, And A Golden Point Was Made

2025-10-27 04:37